“From my training with Soujeesh, the Mohawk Healer, I felt sure this procedure could only push him closer to death…” Janet Blythe, 1815, Never Far

Plants and natural materials, considered medicinal ingredients, promoted replenishment and balance(1) for the sick among the First Nations people of North America. This healing philosophy, fostering therapeutic effects on the body, was extended to Europeans when they became sick after arrival in Canada. Treatments were mostly edible, passed down by Healers from the previous generation. Healing resulted from consuming the plants they harvested and prepared in anticipation of ailments to be treated.

In contrast, the medical care of European physicians of the 1800’s (and earlier) routinely applied bloodletting by attaching living leeches to the skin their patients. Existing belief was that toxins in the body must be siphoned off through systematic bloodletting to prevent or treat infection and disease. Sometimes the application was so exuberantly applied that the patient succumbed to the bleeding.

Jacques Cartier spent the winter of 1535-36 icebound, on the St.Lawrence River, at an Iroquoin Village of Stadacona (present day Quebec City).(2) One-by-one his men grew weaker with incapacitating joint pain, bleeding gums and bruised discoloured skin. The cause was then unknown, but, as a sailor he recognized the onset of the dreaded scurvy, that could sometimes kill up to 50% of the crew on a long sea voyage.

As an offering of peace, the Iroquois Leader, Donnacona, prepared and offered them a tea made from the leaves of a white cedar tree. Preferring to die quickly from poison rather than slowly through scurvy, Cartier drank it and soon felt better. Within 8 days the men were restored. Unfortunately, come Spring, Cartier took Donnacona and 9 others of his village back to France to meet the King of France. All but one, a young girl whose fate remains unknown, died in France.

In France, they would have encountered small pox, measles, mumps and other ailments for which they had no immunity. They also had no access to familiar plants and therapeutic materials.

Eventually these diseases would ravage the Canadian Natives People, but first another mysterious and peculiar sickness was imported, primarily to the Niagara and Rideau regions of Upper Canada. Fever and Ague, a malaria characterized by intermittent chills, fever and eventual anaemia, erupted sometime around the 1780’s, disappearing around the 1840’s. Now known to be carried by mosquitos (genus Anopheles), it was either brought to Upper Canada by infected British regiments from the disease ridden Caribbean colonies, or by United Empire Loyalist relocating from the southern United States(3).

Commonly referred to as the Swamp Fever, under the mistaken belief that it was the result of bad swamp air, it affected more than 60% of settlers in Upper Canada. Another mistaken belief was that the Native Peoples were immune to it. They were not, and also suffered. But they had already learned to reduce their exposure to the carrier culprit, the mosquito(4). Smoke of smudge fires repelled the pesky insects, as did tossing sweetgrass into campfires fire, coating one’s skin in mud and setting up camp in drier areas where the mosquitoes did not breed(4).

In the 1790’s Col. Stephen Burritt having cleared some land near the Rideau River and built a shanty, was stricken with Ague, along with his wife. Laying helpless for 3 days, without fire or food, they would have died had not Native People, traveling through, saved their life.

Leaves and root bark of the Sassafras tree (also called the Ague Tree), were boiled in a tea and consumed to address the symptoms. The suffering settlers did not know that Sassafras had carcinogenic effects, but in the short term, it did provide them some relief.(5)

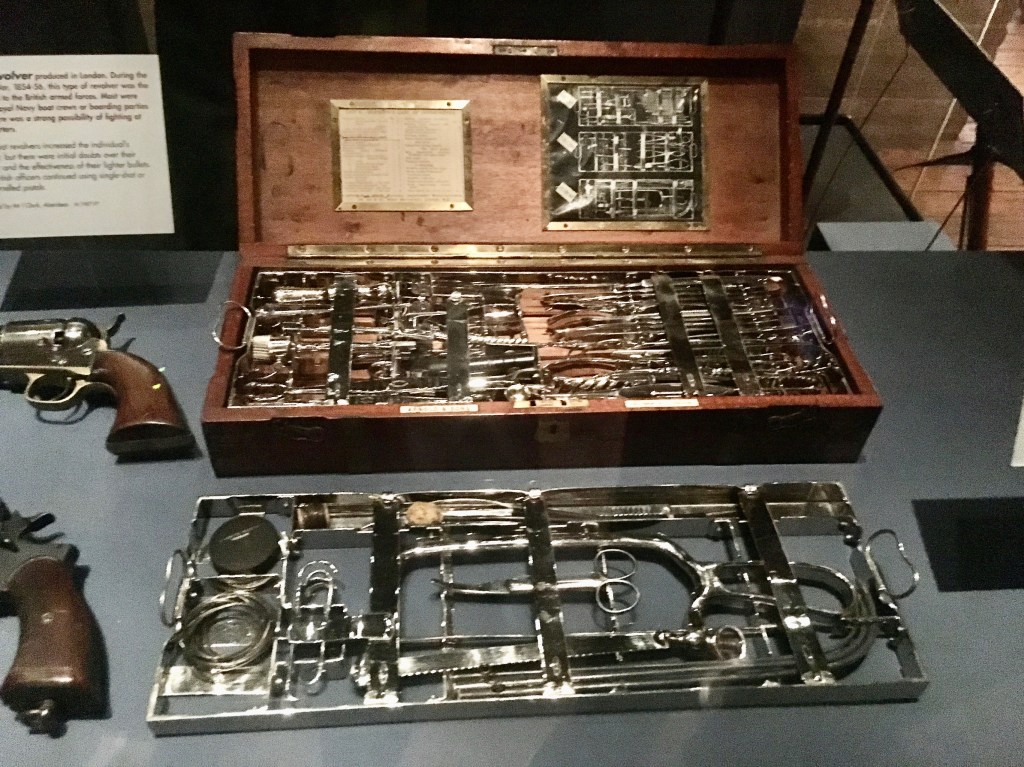

Settlers, mostly refugees, had little choice but to persevere and heed the medical wisdom of the Native People. Those providing European style medical care had little to offer since they were mostly demobilized medical surgeons, with skills acquired on the battlefield. Ill-equipped to meet the needs of the settlers, they were trained to provide immediate medical care on the battle field. Amputations and cauterizations were their speciality, not long-term care, specifically infection protection.

During the War of 1812, Tecumseh, the Mohawk Military leader, was accompanied by a Shawnee healer, to address the needs of his forces. Upon observing the slow healing of wounds sustained by Thomas Vercheres de Boucherville at the earlier Battle of Monguagon in Michigan, the services of his healer was offered and cautiously accepted.

“My Indian doctor returned the next day and started with his herbs. Ten days later the wound was healed and I was able to resume my duties,”(6) Vercheres was pleased to report.

The willingness of those European military doctors to implement Native medical practices is an example of cross-cultural exchange. The Settlers were already aware of the benefit.

Mary “Granny” Hoople was the first “doctor” in what is now Stormont, Ontario. She learned traditional Native healing practices when taken prisoner by the Delaware people, as a child. She applied this knowledge, when she came to Canada as a Loyalist, before the appearance of formally trained physicians.(7)

As did “Aunt” Betsy Stark, first white woman born in the Clarendon Township of the Ottawa Valley. Little is known of how this pipe-smoking trouser-wearing woman acquired her special healing ability, but with faith, she shouldered the medical emergencies of this remote community. Though she was the mother of 8 children, most of the children of the township can credit their arrival with her help.(8)

A reference to Laura Secord should be made here, because of the inferences made. While nursing her wounded British husband (not yet recovered after a year), she overheard plans being made by American soldiers occupying her home and undertook a brave trek to give a warning that undoubtably contributed to Canada remaining an independent democracy. That local Native people both recognized and assisted her indicates an ongoing relationship of mutual benefit.

Neither Women’s history nor that of the Indigenous people was considered worthy of note at this earlier time. Little has been recorded of their lives. Every Laura Secord’s contribution went unrecognised until 1860 when, destitute and widowed, she was awarded a paltry 100 pounds ($10,000 CDN equivalent today) for her contributions to the war. Therefore, we must glean from what has been recorded, and infer from what is left out.

Although Healers Janet Blythe and Soujeesh, her Clan Mother, of my books Never Forget and Never Far, are fictional characters, their story is inspired by actual circumstances around the settlement of Upper Canada. I have read ‘between the lines’ in my research and brought forgotten/omitted heroic lives into reality. Warrior Women deserve to be honored.

- Julian A. Robbins, The International Indigenous Policy Journal, Vol.2, Issue 4, Article 2, October 2011, Traditional Indigenous Approaches to Healing and the modern welfare of Traditional Knowledge, Spirituality and Lands: A critical reflection on practices and policies taken from the Canadian Indigenous Example

- Nancy J. Turner Indigenous Peoples’ Medicine in Canada, The Canadian Encyclopedia, May 1, 2019

- Charles G.Roland, Malaria, The Canadian Encyclopedia, January 2015

- Alex Berezow, Sweetgrass: Like DEET, Traditional Native American Herbal Remedy Acts as Mosquito Repellant, American Council of Science and Health, November 2, 2016

- Charles G.Roland, MD Health and Disease among the early Loyalists in Upper Canada, Can.Med.Assn. Vol128, Mar 1/83

- Gareth Newfield, Surgeons of the 41st Regiment of Foot during the War of 1812, The 41st Regiment of Foot, Canadian War Museum, 2007

- Upper Canada Village Cemetery-Hoople, findagrave.com Mary “Granny Hoople” Whitmore Hoople

- Laura May Harris, Pastures Green, 2008, Lulu Press