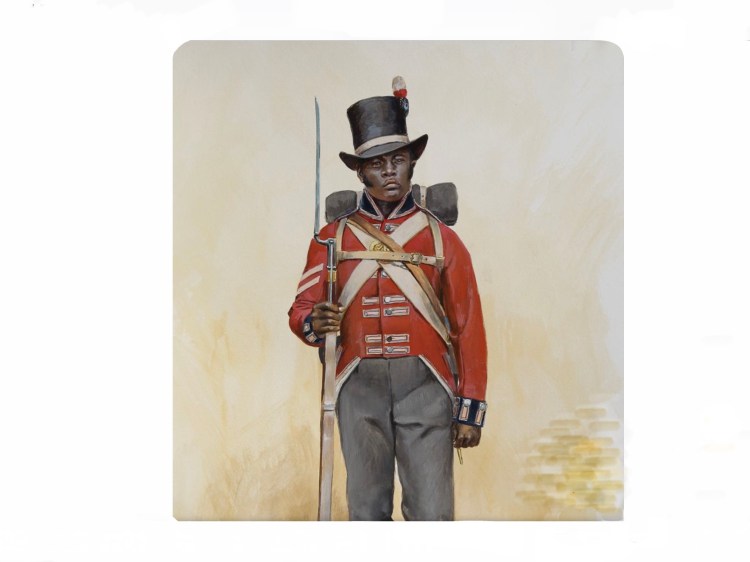

With the American Revolution, Napoleonic Wars and colonial expansion, British Military needed desperately to augment their forces. In the 1790’s Black soldiers were proposed as a possibility, strong men suited to harsh colonial climate.(1) In addition, a well-disciplined armed force of former slaves would encourage slave rebellion in the new American Republic.(2)

Lower ranks were filled with Creole and African slaves, purchased from West Indian plantations, or ‘rescued’ from the middle passage on their transportation to America. After much debate, under the Mutiny Act of 1807(3), Black soldiers were considered freemen, recognised as any white soldier, with pay, pension and land allowances in exchange for service.

In 1809 a young black man was plucked from the streets of Bridgetown, Barbados. He was only 15 and he remained in the military for 29 years, serving in the Canadas. From the War of 1812, through to the Mackenzie Rebellion (1837-38), he defended the British Colony of Canada.

He married an older Irishwoman, was awarded an allotment in the Ottawa Valley, which he registered in his wife’s name, and left at least 4 children, from whom I descend.

This was the beginning of my family’s Canadian Military service.

My grandfather was wounded at Vimy Ridge during the First Great War, the ‘War to End All Wars’, a great uncle lies buried in the Somme. Other’s returned to have sons answer the call to serve in the Second World War. My father endured North Africa, Ortona, Groningen, Germany, serving in the reserves until the Korean War. An uncle remained in the services until the mid-60’s.

I’m a product of the ‘Baby Boom’ post-war celebration of return to peace. I grew up in a society, shadowed by war, attempting normality. The Canadian Legion was our social center.(4) Cousins held their wedding receptions at the Legion Hall. Funerals were catered, grave stones provided and scholarships funded by the Legion. Every Christmas, the Legion Hall held a much-anticipated party for children, where a ruddy-faced Santa gave out inexpensive gifts, and we played musical chairs, while mothers served up pickle and egg salad sandwiches.

Our TV was ‘donated’ to cover my dad’s bar bill. It sat in the Legion bar for 10 years watching over the smoke-filled hall where veterans drank from snub-nosed bottles, sharing the unspeakable. They’d survived, this was their trauma counselling, for PTSD was not acknowledged. The Legion was always there for them; a home for the veteran in every Canadian small town.

The bleeding neighbour, running naked through the streets mid-winter, brandishing a knife, was quickly subdued, taken away to rest, and his family supported. Drunken outbursts were forgiven, fights broken up, nothing was ever spoken afterward, for we endured stoically.

My uncle displayed a German grenade and pistol in his glass liquor cabinet. A boy would have known the model, boasting with bravado. Boys boasted of their Dad’s battles. I didn’t.

“Did you ever kill anyone in the War, Daddy?” I asked instead.

“Hell no,” he assured me, “I hid my arse and tried to stay alive.” Yet, he refused to hunt anything other than partridge, citing, “Looks too much like a human!”

And then there was that thick German leather belt that he slapped against the wall, whenever we were rowdy and disrupted his peace. “Better the wall, than you,” he‘d snipe.

Years later, my sister inquired of the Canadian War Museum if they would be interested in the ‘Belt’. They declined. “We have boxes full of their war trophies—they all brought something back.” Stripped from the dead, proof of survival, something to pass on to the next generation.

Summer vacations were an adventure led by a man whose fear had been burned out of him. Without planning we set off for two weeks, driving ‘winter roads’ deep into the bush, sleeping in our car where tenting wasn’t possible. Thousands of miles we travelled, crossing into the ‘States’, dropping in unannounced on veterans. North America was a safe open road.

My father was fascinated with the War of 1812. Annually we visited Canadian war sites, giving respect to suffering endured, on our land, over a century earlier. He’d seen war’s cost in the villages of Italy and Holland. He knew what had transpired here, in Canada.

Fearlessly my father also took us to Harlem and a burning Detroit in the mid-1960’s. I now understand this as homage to a young black man, long buried in the Ottawa Valley, who fought for dignity and opportunity. A man from whom many veterans descend.

I am a descendant of a Canadian Veteran.

I submit, that although the Canadians are not a war-like people, they are a fighting people, none better. — Leslie F. Hannon(5)

- National Army Museum, nam.ac.uk. The West India Regiments

- Rosalyn Narayan, Creating insurrections in the heart of our country: fear of the British West India Regiments in the Southern US, Taylor & Francis Online (Vol.39, Iss. 3), August 21, 2018

- Dr. Lennox Honychurch, Slavery Reparations: An Historian’s View, BBC Caribbean.com, March 30, 2007

- The Royal Canadian Legion, legion.ca

- Leslie F. Hannon, Canada at War: The Record of a Fighting People, McClelland and Stewart, 1968