Quebec of the 1930’s was still colonizing crown land, awarding lots of 100 acres property in exchange for clearing and residing on the land for a pre-determine inflexible time period. This Abitibi-Temiscamingue crown land was within the unceded territory of the Algonquin people (2) and part of the Ottawa River drainage basin.

There was no public school option in Quebec of the 1960’s. Therefore, the Protestant School system provided the only alternative to French Roman Catholicism. Post-WW2 refugees introduced diversity of language, culture, colour, and creed merging within a common English Protestant education system.

Ukrainians, Poles, Germans, Lebanese, Indigenous, Metis, West Indians, East Indians, free-thinking Roman Catholics and even a few Anglo-Saxons protestants. Our school uniform failed to hide economic disparity: socks held up by elastic bands, thread-bare shirts and coats, scuffed shoes and kitchen haircuts. Professionals, miners, service people, subsistent farmers and rugged individuals dwelt together, in this northern mining town.

One particular school group stood out in this disparity, for their fierce loyalty to each other. Defiant, gritty and predictably late because of road conditions, they poured from a school bus. The rest of us ‘townies’ had to walk to school through omnipresent smelter haze. At the close of school day, they badgered the driver for mercy and wait for those poor individuals doomed to detention by a particularly vigilant science teacher. That battered bus was their sole means home, 13 miles out in the bush.

These were the Farmborough people (1), the stoic remnant of a 1930’s settlers from a depression-era scheme to provide opportunity to economically ‘disadvantaged’ people of Southern Quebec: slum clearance—to put it bluntly—of out-of-work factory workers.

“They pulled us straight off the streets of Montreal and Quebec City,” reported a Farmborough resident, Herbert Moyle(1).

Both Roman Catholic (RC) and Anglican (protestant) churches were supportive of this ‘Back to the Land’ scheme as a means to strengthening the grip on their faltering congregants and provide opportunity. Taking a lead, RC settlement began to populate Abitibi in the 1920’s. This colonization is vividly described in the 1993 TV series, ‘Blanche’, the story of a frontier nurse ministering to settlers while battling the RC church’s dominance over struggling lives.

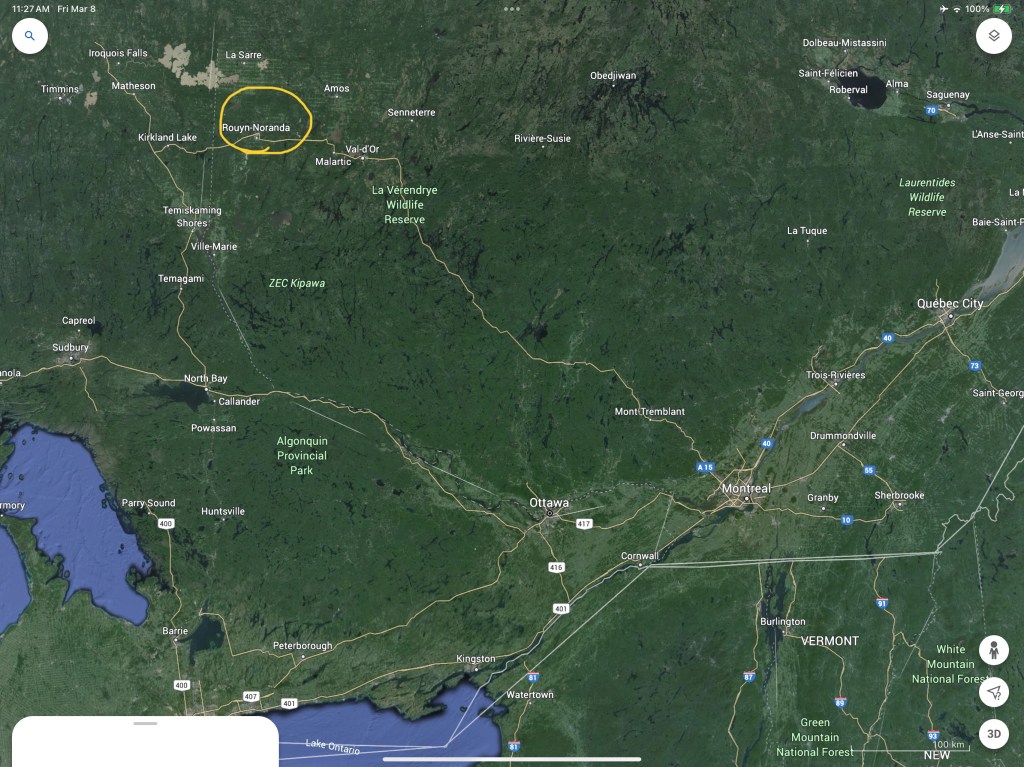

Ten years later, the Protestant Colonization and Land Settlement Society of the District of Montreal began their colonization project. On August 5, 1935, 25 settlers arrived by train in Rouyn.

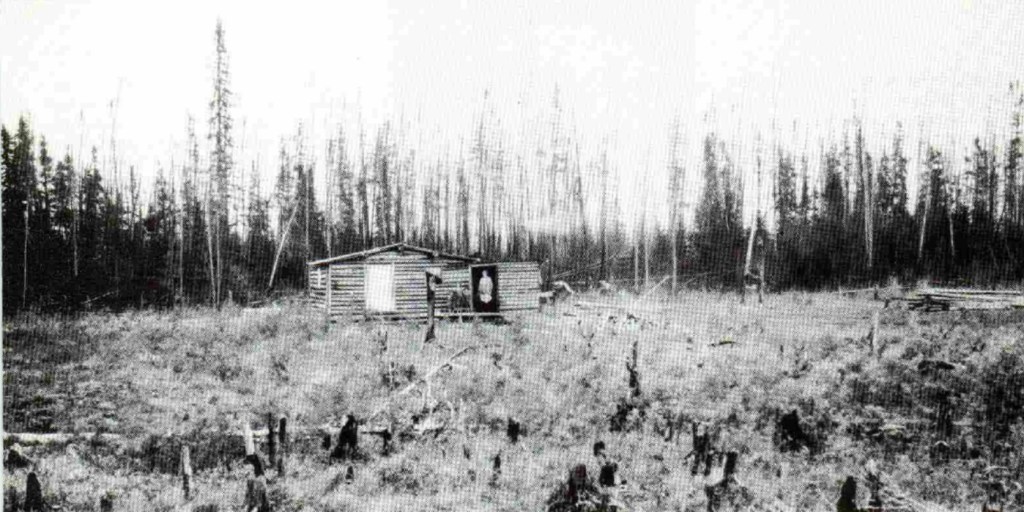

Trucked in, they were let off where the dirt road ended, 3 miles west of Farmborough. Axe in hand, they followed narrow paths to their 100-acre allotments.

With only tents to live in, they were each expected to clear the bush, plant a farm and build a log house in time for winter. This was ‘black fly’ season, the ground muddy, and the city-bred men were inexperienced for such a formidable endeavour.

Abitibi homestead

The following year, 100 more settlers arrived and the colony began to take hold within the bush. Settlers were awarded $300 upon building a barn and could supplement their income with a small wage by working on local road construction.

Being the last to colonize, the Protestant tracts were not a fertile as that of the earlier RC settlements. Top soil was only 2 inches deep over a layer of clay.

Poor quality of wood for house construction, and a short growing season with frost in June and July added to the settler’s hardship.

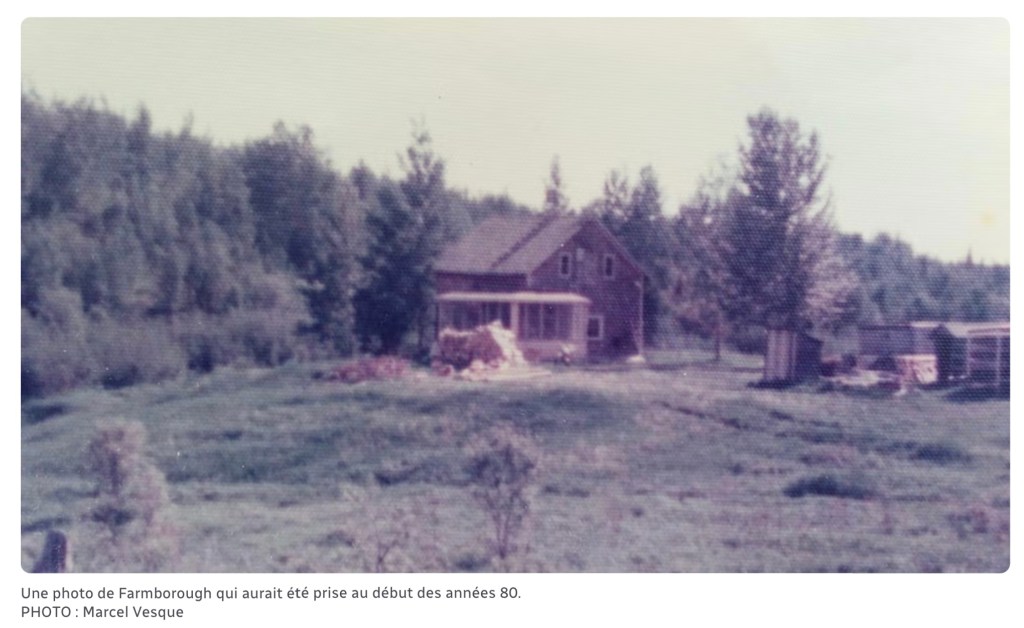

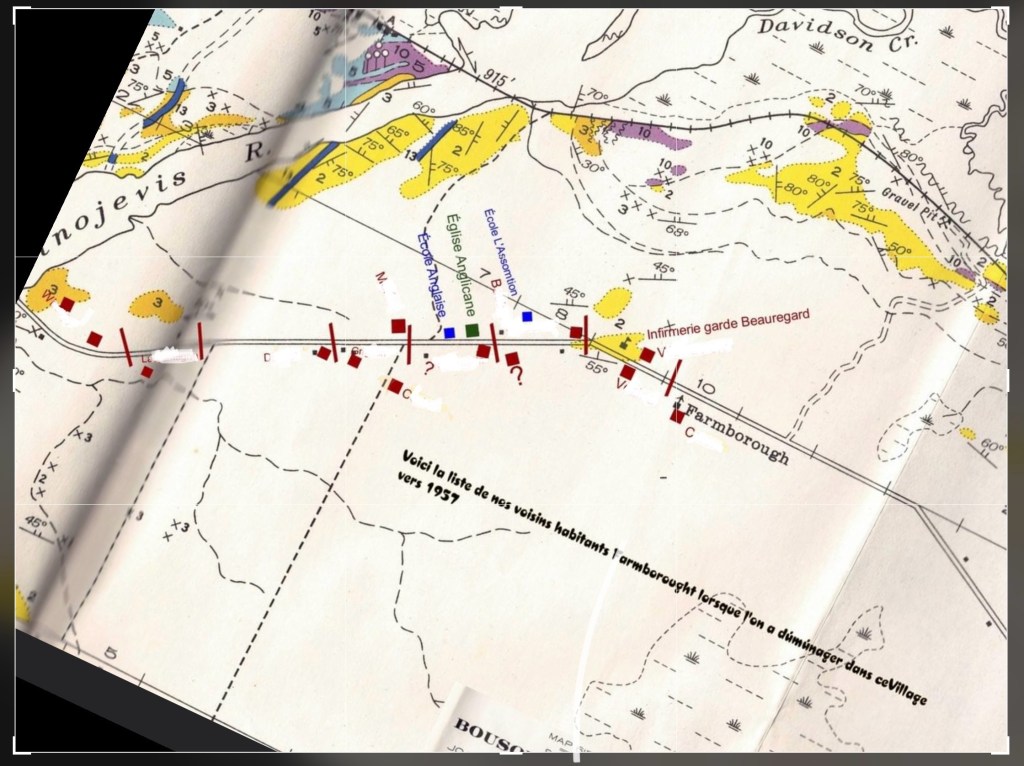

Yet, by 1937, a Protestant School and St. Mark’s Anglican church were completed. These buildings served as post office, dance hall and, twice yearly, a second-hand market (3). The Anglican colony struggled on, under the spiritual care of Reverend Gartrell, until he contracted polio, and then by Reverend George Loosemore, of St. Bede’s church in Rouyn.

In 1940, about 400 families were established in the Farmborough settlement.

“Life was tough but we survived,” said Ralph Hall, a 1936 settler (1). “There weren’t no fun in it, only what fun you could make out of it yourself.”

“We had some pretty good times,” reflected settler Herbert Moyle (1), 4 decades later, “because misery likes company.”

With the onset of world war, Farmborough’s population began to decrease. Settlement provision did not allow absence for military service. Since most of the settlers were mostly 3rd or 4th generation loyal English Canadians, of British ancestry, this was a serious lack of foresight. Property was confiscated despite obvious improvements, and the settlers received only $30—their original deposit. Remaining settlers were able to supplement income working in the mine or logging camps.

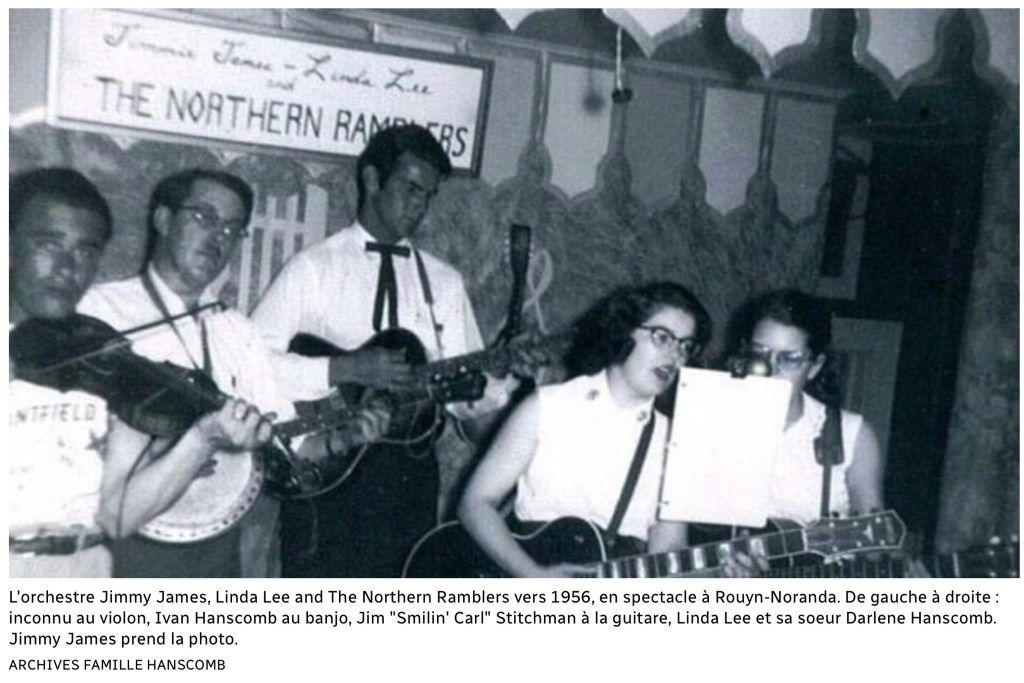

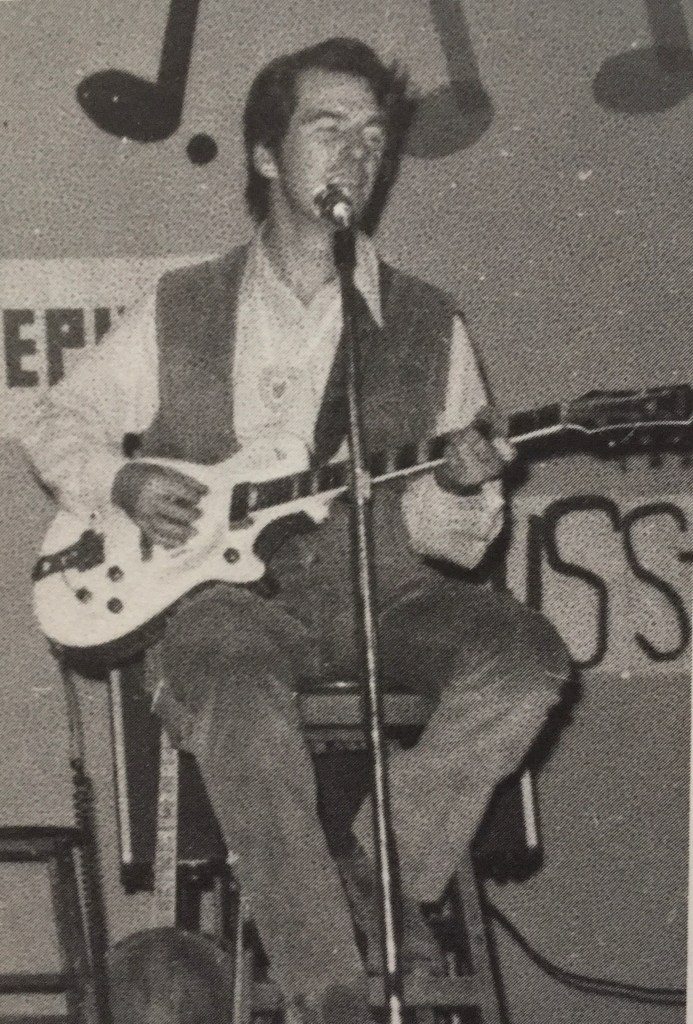

The community bonded with music, dance and protective protestant faith (another story to be told, someday). Soon, Farmborough music spilled out to the benefit of others eking out life in the north.

Lynda Lee Hanscomb and her sisters, Darlene and Jean sang with the ‘Northern Ramblers’ band, that included family friend Jim Stitchman and their father Ivan (4).

James Hines migrated to Farmborough, from Montreal in the 1940’s, with his family, in search for a better life (5). Borrowing Lynda Lee’s guitar, inspired by country music, he began singing under the name, ‘Jimmy James’. During the 1950’s, with his band ‘Les Candy Canes’, he’d signed with Columbia records, toured, and achieved both Toronto hit-parade and French country music fame throughout Quebec. He’d also married Lynda Lee.

By the mid-60’s (my time) only around 65 of the original settler families remained. Sunday afternoon services were still held at the Anglican church, presided over by the Noranda Anglican church of All Saints. St. Bede’s of Rouyn had closed as had the Farmborough and George Loosemore schools. If going through a rough time, one could find inexpensive housing, or temporarily squat on abandoned Farmborough homesteads.

We were also fortunate, to have Jimmy James and his band to sing at school concerts, when he was not on tour. This privilege of Nashville caliber entertainment, was because Jimmy James Jr. went to our school.

In 1971, the Quebec Provincial government cancelled colonization grants, and the Protestant Colonization and Land Settlement Society ceased operation (1). Colonization land allotment ended.

“There’s no way this place should have been opened up…there’s no *** way to do anything with this land,” complained a long-time farmer in 1975 (1).

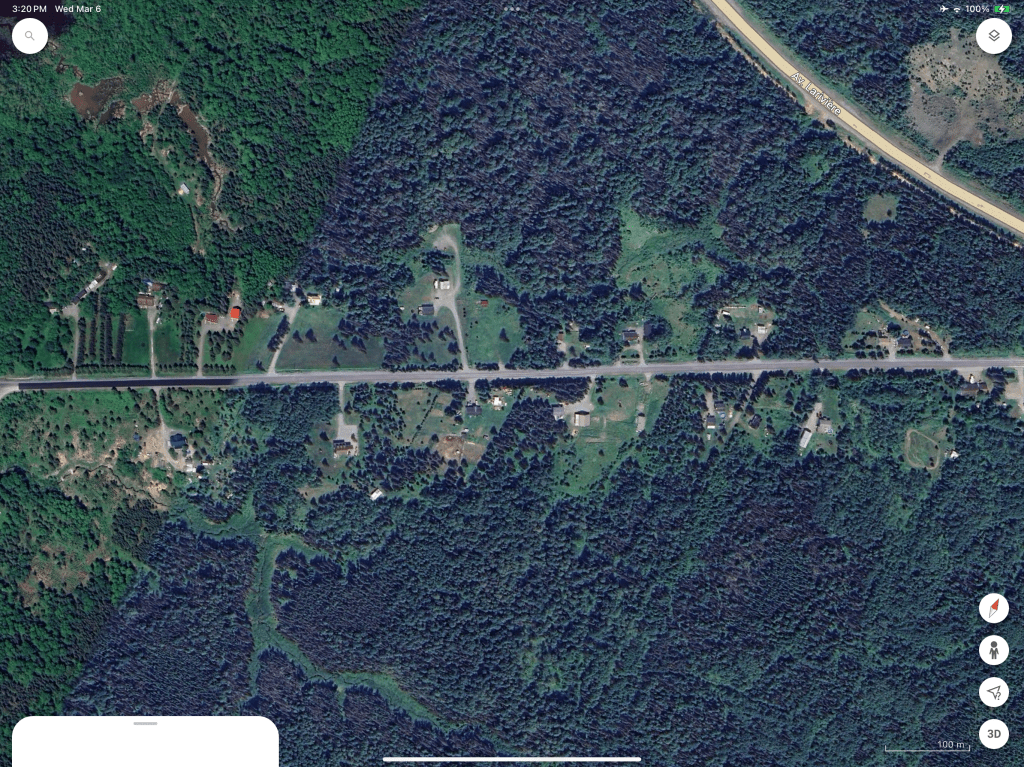

Side by side mapping of 1950’s Farmborough , showing location of Anglican Church and school with present day google map of existing buildings.

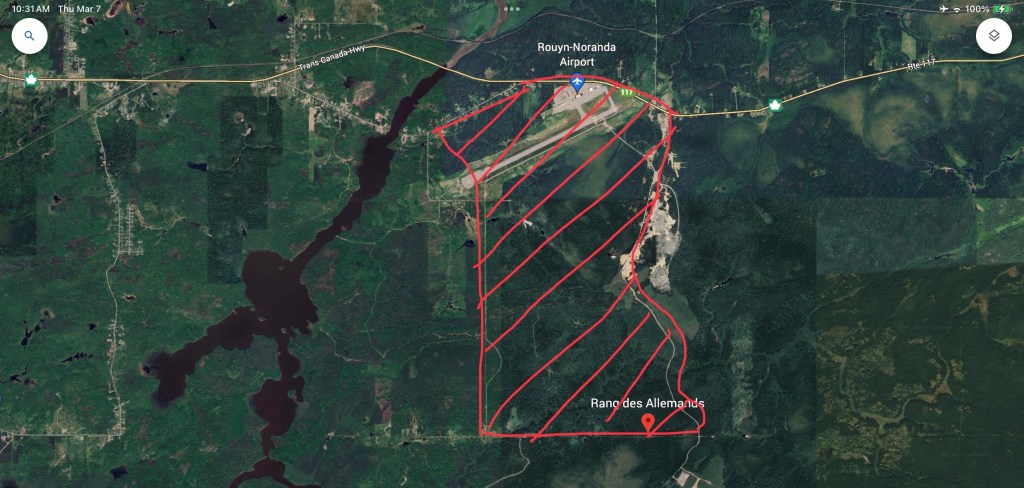

When I last passed through Farmborough, none of the original settlers nor their families remained. The bridge and highway had been rebuilt further north on the Kinojevis River. Anglican church and school had long-been razed and property unrecognizable. Rouyn-Noranda International Airport covered part of the settlement, with bush regrowth and newly constructed houses reclaiming much of the rest. Media search only revealed (7) Roman Catholic colonization and a nearby squatter community, near Malartic, burnt down in response to encroaching criminal activity.

Farmborough may be erased, but I can never forget the people.

These stoic pioneers endured much, seeking a better life—an example to be remembered.

Approximate location of Farmborough settlement / settler and child clearing the land.

references:

(1) Farmborough Broke Backs and Dreams, Claude Arpin, The Montreal Star, July 30, 1975

(2) Wolf Lake First Nation, 20th Century. @wolflakefirstnation.ca

(3) Chronique histoire: le village disparity de Farmborough, January 27, 2020, Radio-Canada

(4) L’histoire de Linda Lee, pionniere de la musique en Abitibi-Temiscamingue, Radio-Canada, Region Zone 8, August 4, 2020

(5) Jimmy James, legend de la musique country d’Abitibi-Temiscamingue est decede, Radio-Canada, December 19, 2014

(6) Google Earth

(7) Facebook, McWatters Quebec. Merci a Grignon Michel, pour la carte de Farmborough

well done

LikeLike