Joseph Bouchette(1) , Surveyor General of Lower Canada, reached Rawdon county’s uncharted northern reaches, on August 24, 1824. To his amazement, he found a thriving community of 200 Irish-speaking Catholic squatters(2) .

Bouchette was no stranger to the Irish. The British colony of Newfoundland had over 200 fishing settlements (total population of 19,000 in 1815) of Irish-speaking Catholics, who composed half of the colony by the late 1700’s(3). ‘Thalamh an Eise ‘, as they’d called their adopted land, translated to Land of Fish.

And in New France, they’d served in the French colonial military, before the British capture of Quebec, in 1759. As early as the 1600’s there were at least 100 Irish-born families and 30 mixed Irish-French Canadian families living in the French colony, as refugees of British rule(14).

During the late 1700’s, Mrs. Mary Griffen, Irish wife of a soap maker, illegally purchased and developed coveted industrial land, of western Montreal. After a prolonged court case, this disputed land was returned to the original owner in 1814. Irish labourer tenants remained as did her name, ‘Griffentown’, upon this urban Irish community.

Joseph Bouchette identified Rawdon’s Laurentian foothills as “waste land of the crown” on his map of 1815.(1-a) Yet brave Irish had crossed Atlantic’s perilous ocean and cleared a clearing in this remote densely forested land and farmed the thin top soil. Canada’s act of compromise with French Canadians gave them peculiar protection.

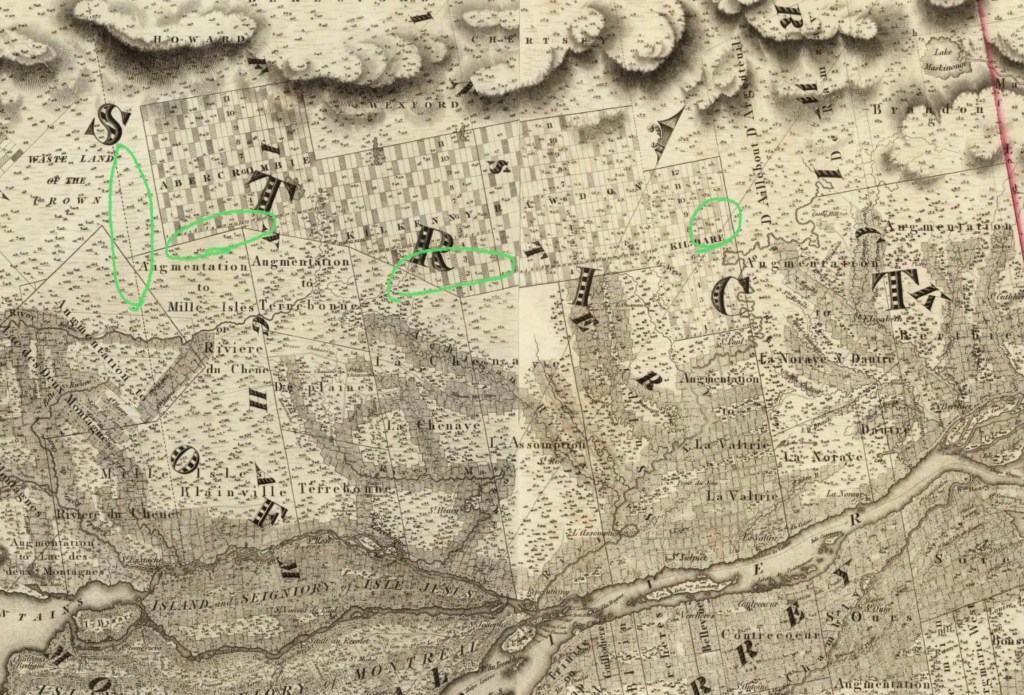

Figure 1: Location of Irish Settlements circled in green) established after Joseph Bourchette’s survey of 1815 (north of Montreal)

For centuries British rule imposed cruel Penal Laws on the Irish in attempt to coerce Roman Catholics to embrace of the Protestant Church of Ireland. Successive penalizations cumulated in Irish Roman Catholics subjected to heavy fines and imprisonment for participating in Catholic worship, death to practicing priests, increased taxation to upkeep the Protestant church, and barred them from voting, holding public office, owning land, teaching and speaking their native tongue. They were not even permitted to play Irish music(4).

By the late 1700’s, under the anti-Catholic King George III, Irish Catholics could not hold office, own an expensive horse, possess weaponry, study law or medicine, hold civil or military office or inherit property, for their land could be readily dispossessed to a nearest Protestant relative. Although some property rights were restored under the Roman Catholic Relief Act (1774), nothing was assured. Severe impoverishment and collapse of the living standard of Irish people resulted. These laws were viewed as eternal damnation of the Irish, for Roman Catholicism interpreted denial of church sacraments as dooming believers to spiritual purgatory.

In Lower Canada, adoption of the politically motivated Quebec Act of 1774, assured freedom of Roman Catholic faith to the larger French Canadian population along with reinstatement of their French civil law (in combination with British criminal law), and protection of language, as well as the existing system of hereditary nobility (seignory system of New France). This legislation purposed to avert an American French Revolution. For the Irish, the Quebec Act provided refuge in Canada.

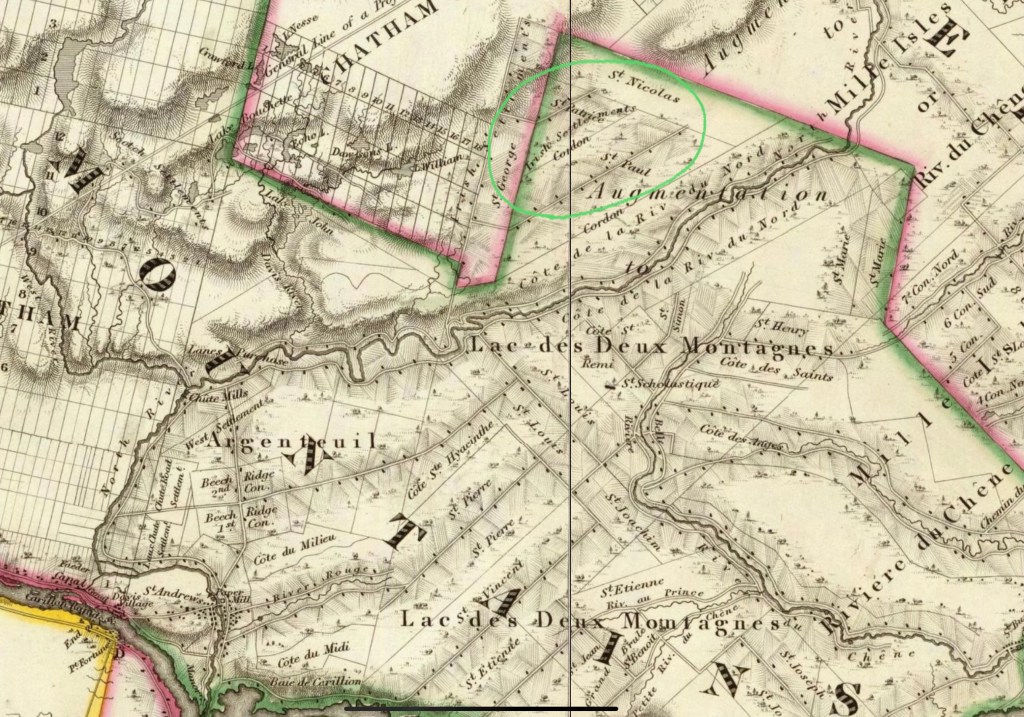

Figure 2: Arrival of Irish refugees to Lower Canada in early 1800’s

Joseph Bouchette’s 1831 survey of Lower Canada(1) identified at least 4 Irish speaking settlements in the Laurentians (Rawdon, Kildare, Kilkenny and Deux Montagnes. See Figure 1). Not all were squatters and not all came directly from Ireland.

From Montreal, Father Patrick Phelan convinced the Sulpician Deux-Montagnes mission to donate land and relocated with several impoverished Irish families to the present-day area of St.Columban in Argenteuil County on the eastern edge of the Ottawa Valley (see Figure 3).

Religious-based schools of these communities, was in both French and English, indicating non-British alignment in their adopted homeland. Freedom of Irish usage was enjoyed, yet religious freedom was of greater priority. Only the community of Kilkenny was Protestant(5).

Figure 3: Irish Settlement, North of Deux Montagnes, Eastern Ottawa Valley (Bouchette’s 1831 survey)

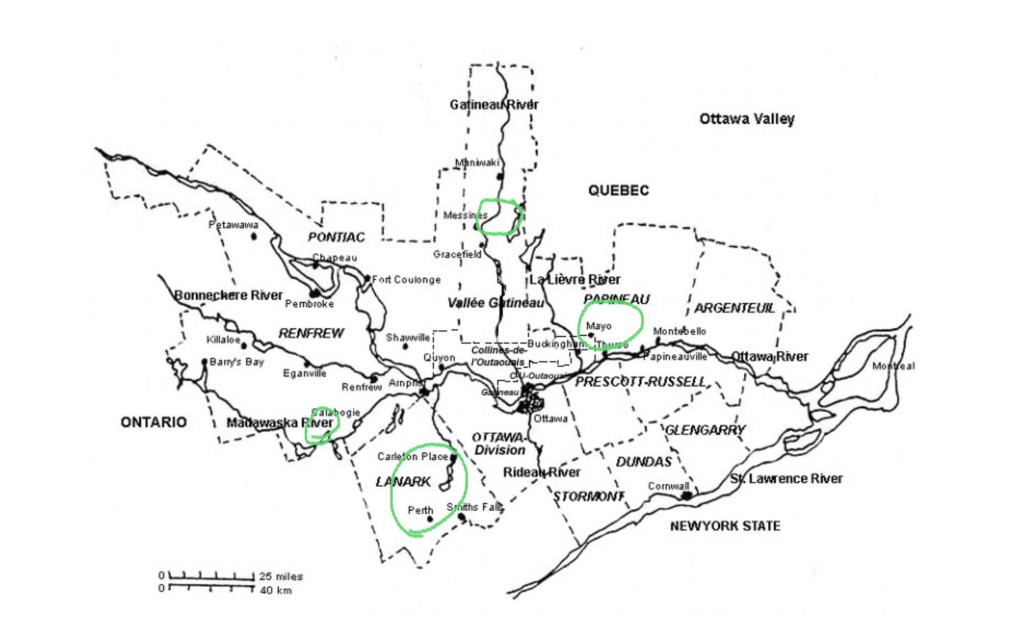

Further to the west, within the basin of the Ottawa Valley, Irish speaking communities settled in the southern Laurentian reaches of Mayo (Papineau county) and Low (north of Gracefield, along the Gatineau tributary of the Ottawa). Farming was difficult, soil thin, yet by supplementing with seasonal lumber work, these communities survived. Originating from rural Ireland, they were familiar with hardship. Of the famine to hit Ireland within a generation, it was reported that a single acre of potatoes could feed a family for a year(6).

Figure 4: Canadian clearing in early 1800’s

The Irish-speaking Catholic village of Mayo, on the Quebec side of the eastern Ottawa valley was populated by pre-famine immigrants (1820-30) who maintained strong connection to their Irish roots. A replica of the Our Lady of Knock Shrine, in Ireland’s county Mayo, was constructed in the late 1880’s as a local pilgrimage site (7)..

To the west, north of present-day Ottawa, along the Gatineau River, lies the township of Low. During the Great Famine (1845-52) founder Charles Adamson Low, a Gatineau lumber baron, populated this area with Catholic Irish settlers(8). Although the true number of Irish speakers is unknown, a 1901 Census of this region reported many instances of Irish as a mother-tongue. Sadly, many children were listed as English speakers, indicating declining use of Irish language.

Saint Patrick’s Mount, north of Lake Calabogie, was also populated by Irish squatters when land surveyors arrived in the 1850’s. These Gaelic speakers had been there since the early 1800’s when seventeen families, joined their shantymen heads-of-family. Other Irish soon settled nearby, with missionary Catholic priests serving this region until a pioneer priest arrived from Ireland in 1842. Saint Patrick Mount’s Catholic devotion is exemplified by a Holy Well, near Constant Creek, blessed in the Irish Tradition, as well as a beautiful old church, and cemetery.

Figure 5: Holy Well of Saint Patrick’s Mount

Over the centuries, this community has been known for producing many priests and nuns(9.). Although located in Upper Canada, this reflects an openness to respect of Catholic rights and Irish language and culture in the early 1800’s.

Prior to 1793, under Irish Penal Laws, Irish Catholics could hold neither military commission nor possess weaponry. Despite this, the British military actively recruited among the Irish between the years 1750 and 1820. Likely the high attrition of forces during the American Revolution and Napoleonic Wars played a role. By 1780 Irish formed a third of rank, of which three quarters identified as Roman Catholic. Passing of the Irish/British Interchange Act of 1811 allowed military Roman Catholics freedom of choice in worship; religious pluralism was provided to military and accompanying family by the British(10) in Canadian military settlements established post-War of 1812, and included Anglican, Presbyterian and Roman Catholic churches. Though freedom was enjoyed, Upper Canada’s Anglophile ruling class remained closed to Roman Catholics, and Irish.

In 1820 George Ramsey, 9th Earl of Dalhousie was promoted to Governor General of British North America. His previous position, as Lieutenant-Governor of Nova Scotia, drew him to the plights of black refugees and indigenous people. Willing to provide rations and land to those who showed ‘shrewd disposition’, he supported humanitarian endeavors of Catholic priests and held enthusiasm for social improvement.

After the War of 1812, Britain wanted to quickly populate Upper Canada to stave off American Republic expansion from the south.

Recognizing Ireland’s unrest and poverty, Ramsey proposed alleviating both the ‘Republican’ and ‘Irish’ problems by offering landownership and participation in local government. To this end, he dispatched Peter Robinson ( a member of Upper Canada’s legislature, and brother of Sir John Beverly Robinson, Upper Canada’s Attorney General), to Ireland to convince impoverished Irish to immigrate to Canada. A promise of assisted passage and 70 acres was extended to all willing eligible males between ages 18 to 45 of County Cork. This region was chosen due to a local severe economic downturn that affected all, regardless of faith(11).

Few responded, at first, for the scheme was viewed as little different from penal transportation to Australia. Resistance was also met by local landowners who resented that he would draw away cheap labour and the most ambitious of workers.

Persisting with a promise of land and supplies, as well as religious and civil freedom, Robinson managed to convince approximately 500 settlers to relocate. Traveling across the Atlantic in two ships, they debarked at Quebec City, continuing on to Montreal by steamboat. From there, they traveled to Prescott on barges and flat-bottomed boats, then made their way north by foot, with their few possessions pulled by oxcart This first group settled in the Bathurst District of Upper Canada (eastern Ontario), including present-day townships of Ramsey, Goulburn, Huntley and Pakenham. Log homes were completed by November 1, 1823.

Figure 6 : Peter Robinson Settlement (shaded in green) of Bathurst District of Upper Canada, 1823. Red dots mark Military Settlement Towns of Lanark, Perth and Richmond.

Spring of 1824 found some land to be too rocky or swampy for farming. Where land was unsuitable, alternative land was supplied. Many stayed on their clearing and farmed; some found work lumbering or on the Rideau Canal construction in 1826(12).

Figure 7 : Irish speaking regions circled in green.

Irish-speaking Roman Catholics populated Ottawa Valley’s backwoods. Land was cleared and churches built. Within a generation English replaced Irish in these communities. Irish immigrants learned English from those whose first language was also not English. Gaelic (both Scot and Irish) was present in the Valley, as was French of les Canadiens. Traces of Irish remain, today, in inflections and expressions known as the ‘Ottawa Valley Brogue’.

Although the ‘Brogue’ is fading from common speech I recall traces in my grandparent’s speech. The town of Shawville was pronounced ‘shovel’, ‘th’ sometimes went missing, replaced by a hard ‘t’, while the ‘t’ was replaced by a ‘d’ (Oddawa instead of Ottawa). Expressions linger such as ‘gidday’, ‘giver yer all’, and ‘be going’. Reminants remain in ‘anyways’ used to end a sentence, rather than ‘eh’, and the use of an inclusive ‘Alls’, Yous’ and ‘let’s get ’er done’(13).

Large Roman Catholic congregations also remain active, throughout the Irish-settled areas. Old cemeteries occasionally display Gaelic on memorials. Ottawa Valley Fiddling and Ottawa Valley Step Dancing have become internationally recognized styles, surviving despite attempts of Penal Law attempts to abolish Irish music and dance. More importantly Irish lives on in the Ottawa Valley, through culture, faith and DNA.

For further appreciation:

The bittersweet tale of an 1830 Irish family’s first Canadian winter is available for viewing at the NFB site. ‘First Winter’, National Film Board of Canada, 1981.

References:

(1) David Rumsey Historical Map Collection, (a)Joseph Bourchette 1815-Topical Map of the Province of Lower Canada, and (b)Joseph Bourchette 1831-Map of the District of Montreal, Lower Canada

(2) Rawdon, The Hills of Home: A History of the Old Rawdon Township, quebecheritageweb.com

(3) The Forgotten Irish? Contested sites and narratives of nation in Newfoundland, Johanne Devlin Trew, Ethnologies (Vol.27, no.2, 2005) re: Irish Newfoundlanders, Wikipedia

(4) A History of the Penal Laws against the Irish Catholics, Sir Henry Parnell, Yale MacMillan Center, glc.yale.edu

(5) The Irish Heritage of the Laurentians, Sandra Stock, Laurentian, quebec.heritageweb.com

(6) John Davis Cantwell MD, A great-grandfather’s account of the Irish potato famine (1845-1850), Baylor University Medical Proceedings 30(3), 2017 July

(7) Knock Shrine, Mayo Quebec, Wikipedia

(8) Gaels of the Gatineau Valley, Danny Doyle, Gatineau Valley Historical Society (Vol45)

(9) Early days in Mount St. Patrick and Dacre, Bill Graham, greatermadawaska.com

(10) Velma, JL Fontena, Some aspects of Roman Catholic service in the land forces of the British crown (1750-1820), University of Portsmouth, @2002

(11) Peter Robinson’s Report on 1823 Emigration to the Bathurst District of Upper Canada (Ontario) Rick Roberts, October 2006, globalgeneology.com

(12) Peter Robinson Settlements 1823 & 1825: A British-Canada Experiment, @ 2018, Derek J. Blout, Lost Branches, LLC

(13) Ottawa Valley Slang: Did you Know the Ottawa Valley has its own Language? (Feb 4/23) Yoair Blog

(14) Lucille H. Camper, Ontario and Quebec’s Irish Pioneers @2018, Durham Press